In 2017 U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) Natural Resource Specialist Samuell Price noticed a clump of vegetation at Cranes Mill Park while he was inspecting the fishing pier.

The water plant was growing around the popular fishing area.

The ranger, who started work at Canyon Lake in 2008, has a biology background with an emphasis in botany. He took a sample because Canyon Lake is not known for aquatic plant growth.

Price’s discovery was the first sighting of hydrilla in the lake. The known aquatic invasive species of plant produces long stems of up to 25 feet in length and forms dense mats of growth on the surface.

He said USACE took notice and started keeping an eye on the situation.

But hydrilla is now growing rapidly in Cranes Mill and other areas on the west side of the lake. Many Canyon Lake residents are now also keeping a close watch on the greenish fronds clogging the waters.

Fingers are pointing at the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD), which oversees and protects wildlife and their habitats, for not doing enough to stop the spread of the invasive plant.

At least several of those speaking publicly about hydrilla’s takeover of certain parts of Canyon Lake think TPWD is making choices that prioritize fishing over other water activities like boating.

Boaters, wakeboarders, kayakers, jet skiers, fishermen, divers, swimmers and property owners who usually defer to TPWD — considered the gold-standard for wildlife management — are questioning the agency’s decisions about how to manage hydrilla.

TPWD is a “controlling authority” on Canyon Lake along with USACE, Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority (GBRA) and the Water Oriented Recreation District of Canyon Lake (WORD).

Canyon Lake was dedicated in 1966 for flood control and water reservation, but USACE boasts on its website that it also offers some of the best water-recreation opportunities in Texas.

Manna from Heaven or Weeds from Hell?

A 2004 article on the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s (TPWD) website describes the invasive as either manna from heaven or weeds from hell, depending on your perspective.

Freelance writer and author Larry Hodge, who worked as an information specialist for TPWD from 2000-2016, wrote: “Aquatic plants in the right amounts can improve habitat for fish and provide food for waterfowl. However, too many plants can overwhelm a body of water. Thick mats of plants can impede water flow and boat traffic, clog water intakes for water and power plants, increase water loss from reservoirs, and lower dissolved oxygen levels by shading other plants and reducing photosynthesis. In extreme cases, overabundant plants can reduce the number of fish a lake can support.”

Surveying the Problem

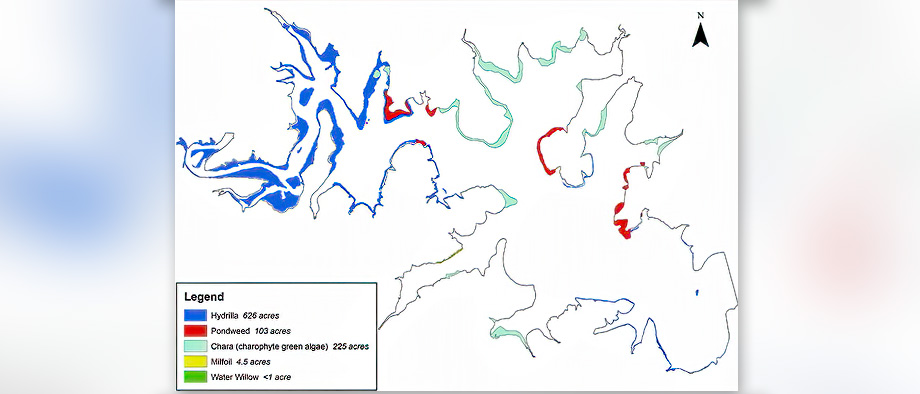

In August 2019 TPWD Biologist Patrick Ireland, who works out of the Inland Fisheries Division in San Marcos, conducted a routine vegetation/habitat survey on Canyon Lake. He recorded the spatial location and extent of the hydrilla in Canyon Lake.

Data collection included finding and recording the location of both submerged and ‘topped-out’ hydrilla that reached the surface of the lake. He found little evidence of the vegetation in the lake.

In a July 2020 report based on 2019 observations, Ireland noted Canyon Reservoir historically lacked aquatic vegetation due to its rocky and steep shoreline. The vegetation survey only detected a small amount of hydrilla in the back of several areas of the lake, he said.

But by 2020, things were changing.

“We have recently — this summer — been getting quite a few reports of hydrilla and other aquatic vegetation showing up in the lake,” he told MyCanyonLake.com in an interview then.

Hydrilla was back thanks to a mild winter and stable water levels in 2018 – but wasn’t considered to be problematic.

An August 2022 Canyon Lake vegetation survey showed similar coverage and distribution of hydrilla to a 2021 vegetation survey.

“At the time of the 2022 survey, Canyon Lake water level was approximately five feet below full pool level,” Ireland said in a Facebook post on Monday. “Lower water levels have exposed greater amounts of hydrilla to the surface relative to earlier in the year and the previous two growing seasons.”

As of October, the majority of hydrilla coverage is confined to the upper end of the lake and remains under the recommended coverage for aquatic vegetation for fisheries production (30% of the total surface area), he said.

Hydrilla covers 10% of Canyon Lake.

Residents React

Asked to address residents’ growing concerns about hydrilla in the Cranes Mill and Potter Creek areas, Ireland angered Cordova residents Bryant Bonner and Travis White with this response, which appeared in MyCanyonLake.com on Oct. 7.

White believes TPWD prioritizes the interests of anglers over others due to the lucrative income it makes from selling fishing licenses

“I have enjoyed Canyon Lake my entire life,” he said. “As a kid I came and swam here, boated here, and we’ve never had anything like this on the lake, ever. What is concerning to me is that you have these officials from TPWD that are more or less talking out of both sides of their mouths…You can’t play with this stuff. And that’s exactly what they’re doing. They’re playing.

“I don’t tell you where to fish or why, why are you telling me where I can take my family to enjoy?”

Bonner said he wonders if USACE and TPWD actually see hydrilla as a positive for the lake.

“I believe, based on numerous biological reports, that it is very destructive and harmful to all stakeholders,” he said in an email after an interview. “I do believe that the governing bodies are slow-playing correcting this situation as they believe it is favorable to anglers yet the anglers cannot fish the infested areas — they cannot navigate their boats into the infested areas. The angler’s voice needs to be balanced with other stakeholders, non-anglers.”

White launched a website, canyonlakehydrilla.com, and a Facebook page, Stop Hydrilla on Canyon Lake, earlier this year to educate the public about the issue and to pressure TPWD into doing more.

Major concerns include:

- Safety — even experienced swimmers cannot make it through the heavy vegetation.

- Entanglement — hydrilla is a nightmare for boat propellers and water intake engines.

- Restricted access to infected parts of the lake including by rescue boats operated by Canyon Lake Fire/EMS (Chief Robert Mikel did not respond to an email from MyCanyonLake.com asking if he could verify claims that hydrilla kept rescuers from reaching a fire earlier this year).

- Snakes that hang out in hydrilla.

- Property values.

- Loss of revenue to local businesses dependent on income generated by water recreation.

“We warned TPWD that navigation would be significantly harmed around Cranes Mill and upriver towards Cordova Bend/Mystic Shores, that hydrilla is a huge risk for swimmer safety (lives will be lost), and that we would no longer be able to use the body of water near Cranes Mill, a place many boaters with children have enjoyed,” said Bonner, who “partnered” with Ireland several years ago and showed him where the hydrilla was then. “The infestation is now heading towards Party Cove, Cordova Bend Mystic Shores and upriver.”

Mystic Shores resident Rob Carty said hydrilla isn’t just heading toward Mystic Shores — it’s already there and getting worse.

“I live in Mystic Shores, above the cove at Boat Ramp #23,” he said. “I see the cove every day. The matting from hydrilla is heavier than ever. And despite some of the claims that I’ve read, our past two winters did nothing to impede the growth. I saw small patches on the surface two years ago, but they’ve metastasized every year.”

Bonner said he warned TPWD three years ago about the dangers hydrilla poses to Canyon Lake and was ignored, along with offers to personally help officials remove hydrilla from the lake.

“The problem has gotten exponentially worse,” he said.

“We missed a huge opportunity to rid the hydrilla once and for all before it had the opportunity to spread to what it is today,” White said.

Bonner disagrees with USACE assessments that lower lake levels are responsible for hydrilla growth.

“The infestation has been here the past three years when the lake pool level was full (909 feet) and the hydrilla still existed and posed a danger to the public,” he said. “The infestation that you see today will survive if the lake level raises to full capacity…it is in the main lake where the depths are 50 feet-plus that you will not see the hydrilla due to the depths and lack of sunlight at the floor. The depths around Cranes Mill and upriver are typically 25 to 35 feet and it grows there when the lake is at full pond level.”

Although USACE Canyon Lake Manager Javier Pérez Ortiz said the vegetation is causing minimal impact on the Corps’ operations, White said hydrilla is known to clog waterways and impede flood-control efforts.

“Basically hydrilla and water cannot occupy the same space at the same time,” he said.

After careful study and conducting lots of research, White and Bonner suggest TPWD should control hydrilla by applying herbicide, which the agency has done in the past.

In the summer of 2021 TPWD treated hydrilla in the Cranes Mill area including the public fishing pier, courtesy docks and Boat Ramp #10.

Bonner said TPWD treats over 20 other bodies of water across the state for hydrilla, and includes this list of approved treatments on its website.

“Why aren’t they doing the same at Canyon Lake and supporting the stakeholders who would like to use the lake recreationally like they are doing across the rest of Texas?” he said.

Both White and Bonner think genetically engineered “triploid” or sterile grass carp offer the best and most-promising solution to the hydrilla headache.

“I think dismissing the use of grass carp in Canyon Lake is a major miscalculation,” he said. “I believe sterile grass carp have been used to control the hydrilla in every lake TPWD has treated. If there is a case where they haven’t used grass carp then what lake was that in? Grass carp are the solution, in my opinion. The problem TPWD has made in the past is putting in too many grass carp in too quickly, like with Lake Austin.”

White said there isn’t a single reported incident of a chromosomally-engineered grass carp turning out to be fertile. TPWD has no reason not to set them loose in the lake.

If TPWD does nothing about hydrilla, they say the plant will continue to spread and reproduce. All it takes is one boat propeller to chop the plant into pieces that drift to other parts of the lake and make more hydrilla.

“What some of the lakes have done once hydrilla is under control is having spotting parties,” White said. “If they see it, it needs to be eliminated.”

Their bottom line?

The longer it takes TPWD to start treating hydrilla in Canyon Lake the more it will cost taxpayers later to clean up the damage it causes.

No Easy Answers

But Price warns there are no easy answers or quick fixes to Canyon Lake’s hydrilla situation.

Earlier this month he joined a team of volunteers cleaning up trash in and around the shores of Canyon Lake.

After USACE consulted with Ireland for guidance on removing hydrilla, Price said the group waded into knee-deep water at North Park to pull out large clumps of ropey hydrilla vines in the hope of controlling future growth.

Price said ongoing drought and lower lake levels are behind current infestations like this.

As water levels fall, the roots of hydrilla plants are exposed and the plant dies. However, low lake levels also allow the sun to penetrate water depths the plant normally would not reach, allowing hydrilla to grow where it normally could not.

Price agrees that hydrilla is creating all kinds of headaches for boaters – he’s dealt directly with stranded boaters.

But hydrilla provides more cover for young fish, frogs, and anything else that is aquatic.

“It provides cover for small fish that are preyed upon by larger fish thus allowing them to mature and reproduce,” he said. “Hydrilla is both good and bad for Canyon Lake.

“There aren’t any easy solutions or pat answers that will make everyone happy and comparing one Texas lake to another isn’t valid. Lake Conroe is nothing like Canyon Lake in many aspects from soil composition, local native plants, water turbidity (clarity), and local weather patterns.”

He thinks introducing genetically modified grass carp into Canyon Lake to eat hydrilla is a bad idea.

“Grass carp do have a massive appetite for aquatic plants such as hydrilla, but they also enjoy many other soft green aquatic plants,” Price said. “They can consume massive amounts of vegetation including invasives like hydrilla and non-invasives you want to keep. They could also be considered an apex predator and not exclusively herbivores. Like many animals, once their main food source runs out, they have been observed eating other fish including bluegill and bass which are smaller than they are. As long as their food source of aquatic plants exists, they will continue to eat on the aquatics usually.”

Carp live between five to 20 years.

“Once they are introduced, you will have to deal with them for a very long time,” Price said. “They are also not a small animal. Some have been recorded to weigh between 60 to 80 pounds and over five feet long, but that is not always the case. A fish of that size eats a massive amount to sustain its body.”

Price said biologists can’t be 100% certain that grass carp genetically bred to be “triploid” or sterile actually will be.

It’s not a risk worth taking.

“This means they carry a chromosome/gene that prevents them from reproducing,” Price said. “Technically speaking, the triploid genetics of the grass carp should prevent it from reproducing and taking over a body of water, but there is also no 100% guarantee that all of the ‘sterile’ carp would be sterile. Not everything is as clean-cut and simple as some would like to believe.”

Herbicides aren’t worth the risk either, he said.

“There are those asking to use herbicides to eliminate hydrilla, but there are many native plants that are potentially susceptible to the same herbicides used to kill hydrilla,” Proce said. “Basically, many aquatic plants would die or be harmed by the herbicide method. Thus, changing the health and condition of the lake. There is no such thing as perfect ‘targeted’ herbicide.”

TPWD will ultimately call the shots on long-term hydrilla management, Price said.

“We have to defer to the experts on best ways in the future. USACE will provide technical assistance and cooperation in order to properly manage hydrilla.”

TPWD Clarifies Its Position

On Facebook Monday, TPWD responded to a comment by White, reiterating that the majority of coverage in Canyon Lake is confined to the upper end of the lake and remains under the recommended coverage for aquatic vegetation for fisheries production or 30% of the total surface area.

“Currently, hydrilla coverage is under 10% of the entire reservoir and abundant open water continues to be readily available. Further, public access and navigation isn’t currently impeded.”

But TPWD is working with other controlling authorities to secure additional funding for limited herbicide treatments in order to maintain public access and navigation.

“Similar efforts to maintain public access may occur in the 2023 growing season, contingent upon water levels and vegetation growth patterns,” he posted.

In a statement emailed to MyCanyonLake.com on Friday, TPWD said it is monitoring hydrilla coverage at Canyon Lake as the plant enters its winter dormancy and growth resumes next spring:

“TPWD coordinates closely with reservoir controlling authorities and local stakeholders to make recommendations, provide data, and review all treatment proposals to ensure consistency with the Statewide Aquatic Vegetation Management Plan.

“At Canyon Lake, TPWD is coordinating closely with the USACE, which is the reservoir controlling authority, is the landowner of the Canyon Lake shoreline, and is ultimately responsible for making the decision on whether any treatment of hydrilla will occur and the specific treatment methods to be used.

“In addition to the reservoir controlling authority, TPWD is also coordinating closely with WORD, GBRA, and other local stakeholders including people who participate in water-related recreation on Canyon, as the appropriate management strategies are identified for Canyon Lake.

“Any treatment plan will consider potential effects on the fishery with the goal of maintaining sufficient aquatic vegetation coverage to sustain the improved fishery, while also considering impacts to other stakeholders and reservoir use.

“TPWD recognizes the positive impact hydrilla can have on Largemouth Bass populations, angling opportunities, and related local economic benefits as reservoirs age, while also recognizing hydrilla can become invasive and negatively impact access to the water, property values, recreational boating (i.e., impeding navigation), and operations by controlling authorities.

“TPWD carefully considers all these perspectives when making recommendations to the controlling authority.

“Reservoirs with hydrilla each present a unique set of circumstances in terms of the potential hydrilla management strategies, and recommendations may range from routine monitoring to targeted treatments, to large-scale integrated pest management strategies.

“TPWD conducts routine monitoring of all waterbodies where hydrilla is present to evaluate coverage, inform management recommendations, and communicate with stakeholders. In determining the potential need for large-scale treatment of hydrilla, a variety of factors are considered, including distribution of hydrilla, primary reservoir uses, observed and potential impacts, the reservoir’s physical and biological attributes (e.g., submerged contour, hydrology, and nutrient loading), adjacent aquatic ecosystems, conservation objectives, and stakeholder interests.

“Each reservoir, including Canyon Lake, is evaluated and managed individually under its own set of circumstances.

“The coverage of hydrilla at Canyon Lake is currently approximately 10% of the reservoir surface area. Although not significantly disrupting recreational uses lake-wide, hydrilla does represent an acute, localized user conflict in the upper end of the reservoir.”

My wife and I were so excited to build our retirement home in Cordova Bend and have a great view of beautiful Canyon Lake. Now our view is not so beautiful because of massive amount of hydrilla. Boating, swimming and other water activities are impossible from our shoreline. In addition I am concerned about the hydrilla reducing my property value. If the hydrilla had been there like now I would not have built on Canyon Lake. The TPWD really needs to get rid of and control the hydrilla. It’s ruined the Lake where I live.

Great article and discussion. In the spring of 2022, I accidentally got my boat too close to the hydrilla near the Cranes Mill Marina. It was “everywhere”. Fortunately, I was able to get to clearer water before jumping in (with a life jacket and spare float tied to a rope) to clear my prop. The growth of hydrilla is increasing. Canyon lake was so clear just a few years ago. I hope something can be done this winter.

The response from some folks clutching their pearls over 10% coverage of Canyon Lake is incredible to me. It is your standard “not in my backyard” response citing life and safety to try and demand of a response from authorities. THINK OF THE CHILDREN. It’s dramatic and overblown. The grass will have years of extensive growth (like this year, exaggerated by the lower water levels) and years where it is almost non existent; see Toledo Bend currently where it went from wide spread to non existent and Choke Canyon to a lesser extent.

TPWD is working to balance the interest of stake holders rather than only listen to a few loud voices comparing apples to oranges. Canyon Lake isn’t your farm pond or even a shallow natural lake where the grass can completely take over.

Tyler, here’s some data from TPWD and USGS.

At Choke Canyon, hydrilla coverage declined temporarily, starting in 2011 when the lake began drying up. The lake is still seriously low — 40% of its 2011 storage levels — but that hasn’t stopped hydrilla from rebounding with a vengeance. Over six years, the surface-area coverage at Choke Canyon increased nearly tenfold, mushrooming from 133 acres in 2015 to 1,150 acres in 2021. What’s more, the 2021 surface coverage is twice as much as it was in 2011, before the hydrilla made its temporary retreat (then 616 acres). Mr. Price describes this die-and-rebound process in the article above.

As for Toledo Bend, TPWD reports that the hydrilla washed away in 2015 due to “high winter and spring inflows.” Whatever the cause, in 2016 TPWD stepped up its herbicide use (thanks to increased legislative funding). This program was still going as of TPWD’s most recent survey in 2019. And it’s worked: As of the 2019 survey, aquatic weeds covered less than 1% of the surface area at Toledo Bend.

Does Canyon Lake deserve the same consideration?

TPWD statements that 10% lake coverage of this invasive is not problematic is not accurate for those residents who live in areas that are 80% covered in hydrilla. The cove where my children used to swim is now extremely dangerous. Grown men have nearly drowned. Multiple boats have been stranded by the weeds in their props and I have rescued several of my neighbors. This policy of waiting for 30% coverage of this invasive is crazy. They need to spot treat those areas that are badly affected immediately before someone is hurt or killed and before it spreads to other areas. They will certainly be the responsible party when that happens if they take no meaningful action now.

As the Canyon Lake area grows in popularity and use, the need to consider the safety and recreational uses of all constituents is growing. The hydrilla growth / coverage in the lake has provided positive impacts for anglers, but the safety and access of boaters and swimmers must also be brought prioritized. In certain areas of the lake, boats can no longer enter the water. Not only is this a limitation on access, but it is also a safety factor for anyone in the water. Finding a viable middle ground is needed.

Good Afternoon, Canyon Lake Residents..I’m concerned and ask we address the Hydrilla sooner vs later…the Guadalupe is DYING! While concerned about using chemicals in a water source, and there’s no one method as a solution, I’d prefer using sterile grass carp in a select area and check on the results. As I mentioned in earlier post, the fishermen need to take a backseat, eventually there will be NO way to boat on the Guadalupe, and worse, someone’s child is going to drown in this weed. Thanks so much.

When I was in high school I used to fish at a nearby farmers lake (with his permission of course). The fishing was not bad and you could always count on getting a few good size bass out of the lake. The lake had a minor problem with hydrilla but you could still avoid it by going to other places on the bank. By the time I was out of high school the lake was completely overtaken with hydrilla. So… while the current Canyon Lake problem might be “good” for the fish, this is short term view. Eventually, the areas currently being impacted will be devoid of fish. In Canyon Lake in particular there was a recent incident where one of our neighbors was nearly drowned when he hopped off his jet ski to pull hydrilla out of the intake. Had his son not been there to help him, there could have been tragic consequences. Action should be taken on getting this situation under control – and keeping it under control – while the cost is still reasonable.

The hydrilla problem in Canyon Lake is getting out of hand. There are portions of the lake that are not usable for recreation and will have a degraded flood control capability. This is also a safety issue for boaters and swimmers. There is nothing being done (intentionally) to appease anglers, but this is only one of the uses of the lake. A compromise plan to address this grown hydrilla problem is desperately needed.